Let’s take a deeper look at what makes Seraphim so unusual genetically, this thing that causes them to transform from a red Satinette color pattern to a pigment free, pure dazzling white – and how does this differ from the white of other pigeons in pattern of inheritance? And what else is going on genetically in Seraphim that makes these Fancy Pigeons different than their breed of origin, the Classic (Old) Oriental Frill? If you are unfamiliar with basic pigeon color genetics you can skip down in this same article to the section called Basic Pigeon Color Genetics and review it before diving into the explanation that begins immediately below. I’ve made this as simple as I can, but the color genetics of Seraphim is a bit complicated.

SERAPHIM COLOR GENETICS:

Let’s start with definitions and descriptions of what we know at this point based upon the known history of the origin of the breed and the color breeding experiments done to confirm its color inheritance. The “Seraphim Color Gene Complex” is a combination of color genes that is unique to Seraphim. The complex is made up of background genes that affect color distribution along with a combination of gene mutations that cause the Seraph to turn white at the first molt. All of these color genes and gene mutations are required for color in Seraphim.

BASE COLOR GENES in SERAPHIM:

SATINETTE PIEBALD: The first two birds that demonstrated the Seraphim Color Gene Complex were hatched from a pair of Satinette Classic Oriental Frills. The first genetic color requirement in Seraphim is presumed to be the basic Satinette pattern of color distribution, a pattern that was created over time using the Piebald mutation(s) and the Dominant White Flight mutation. Below is a photo that shows the Satinette distribution of color and pattern in a Classic Oriental Frill:

You will note that the Satinette Oriental Frill is white except for the wing shields (the small shoulder feathers overlying the long flight feathers), the tail feathers, and the tail covert feathers (small feathers overlying the base of the tail). The white in the head, neck, chest, body, feet, and legs comes from Piebald genes. The areas of white have been relatively fixed in place by generations of selective breeding but can only be maintained by careful attention to detail, as Piebald is a “fuzzy” trait, i.e. it doesn’t breed true consistently, so it’s difficult to get a perfectly marked Satinette; often there will be a stray, colored feather in the field of white. The Piebald white color distribution over the body makes the Satinette Classic Oriental Frill look like it’s wearing a tuxedo.

DOMINANT WHITE FLIGHT: The ten long flight feathers are also white in Satinettes, and this comes from a gene called “Dominant White Flight.” (See above photo.)

IN SUMMARY: The white areas in Satinettes come from the gene mutations of Piebald and Dominant White Flight. The colored areas seen in Satinettes are always one of the basic sex-linked colors that all pigeons carry, such as blue/black, ash red, or brown. (The bird shown above is blue/black.) The color pattern (feather markings) may be stencil, barred, T-check, spread, or any other pattern. The Satinette color distribution over the body is the underlying basic color distribution in all Seraphim, but it is always hidden (masked) in the adult Seraph because of three additional color changing mutations.

COLOR CHANGING MUTATIONS:

The three additional color mutations in the Seraphim Color Gene Complex are overlaid on the Satinette color distribution. These are unimproved “Recessive Red,” “White-Sides,” and an as yet undefined “Tail-Whitening” mutation.

RECESSIVE RED: Recessive Red is a non-dominant autosomal color gene that turns all of the colored areas on a pigeon red when it is inherited from both parents. The red hides and covers all other color genes the bird may have.

WHITE-SIDES: The White-Sides mutation, when inherited from both parents along with Recessive Red, will cause red pigment in the wing shield to disappear with successive molts, gradually turning the shield white. The mutation is probably a genetic “switch” that turns off the production of red pigment feather by feather.

TAIL-WHITENING: The “Tail-Whitening” mutation has not been sorted out, but it is also probably a genetic “switch” rather than a gene. When inherited from both parents, it turns the tail white with successive molts.

In the case of Seraphim, the Recessive Red gene is initially turned to “on” to produce pigment in a Satinette distribution, but then turned to “off” by the White-Sides and Tail-Whitening gene switches to create the absence of pigment in the wing shield and tail of the adult. So, the baby Seraph always starts life with the Satinette color pattern in Recessive Red.

A strange thing happens, however, with this combination of genetic mutations in Seraphim. Rather than gradually losing red pigment with successive molts, the birds lose ALL red pigment with the FIRST molt. Linkage of the White-Sides and Tail-Whitening genes and gene switch mutations may play a role in this unusual transition from red to white.

**Interestingly, in Seraphim, juveniles which have mismarked red pigmented feathers in areas that are supposed to be white based on the Satinette Piebald color distribution, still molt completely to white, suggesting that the “controllers” that stop pigment production in the wing-shields and tail are also having a broader effect on the whole body, head, and neck. It thus may be that the Satinette color distribution – presumed to be essential – might not actually be essential for a Seraph to turn pure white. (There may be another explanation. See “Important Note” a few paragraphs below.)

MORE DETAILS ABOUT RECESSIVE RED MUTATION: The Recessive Red mutation is a recessive gene on one of the regular (autosomal) chromosomes which, when transmitted from each parent, overrides or masks the primary Ash Red, Blue, and Brown sex-linked color genes that normally determine the basic color of all pigeons. It usually masks feather pigment patterns as well, with exceptions. Birds with a pair of these recessive genes will appear “red,” while birds with only one of these genes will show the color carried by their sex chromosomes – Ash Red, Blue, or Brown. Recessive Red is epigenetic to all other colors except Recessive White and albino, i.e., it hides or “paints over” (dominates) them so they are not seen. However, Recessive Red does not “paint over” white piebald areas or stencil patterns. Recessive Red Satinette birds will thus appear red in the wing shields and tail regardless of the underlying sex-linked color of the bird, and they will show a spread, barred, or lacewing pattern and a lace tail or spot-tail pattern. The “Dilute” gene will modify the red color to yellow if present. Since all Seraphim are Satinette as a base color pattern as well as homozygous for Recessive Red or Yellow, they appear at first feather to be marked as Red (or Yellow) Satinettes. Seraphim babies are never white.

MORE DETAILS ON THE WHITE-SIDES MUTATION: The “White-Sides” mutation is fully expressed ONLY in birds homozygous for both it and Recessive Red or Yellow (Dilute Recessive Red), and it is probably not a gene, but rather a gene controller or switch that links to the Recessive Red gene. Pigeons of any color or type may carry the White-Sides trait invisibly, but if a Recessive Red pigeon inherits one copy of the White-Sides mutation, its wing-shield will turn partially white or “rose” with the first adult molt and that pattern will remain; if it carries two copies (one from each parent) the wing shield will turn completely white with successive molts.

MORE DETAILS ON THE TAIL-WHITENING MUTATION: The “Tail-Whitening” mutation is a separate mutation that causes the tail to stop producing pigment and turn white with successive molts. The mutation probably affects a genetic controller switch that sends a signal to the pigment production gene to flip to “off.” In experimental crosses of Seraphim with pure Recessive Red pigeons, crosses of the F1 and F2 generations result in birds with a mix of rose, red, and White-Sides in the shield with either red or white tails, proving that the White-Sides and Tail-Whitening traits can be split out from each other. It is clear then that the gene controllers for turning on the White-Sides and the Tail Whitening mutations are different. In Seraphim, however, the whitening effects of the two mutations are switched on together all at once early in life rather than being expressed over multiple successive molts, but why? More on that below:

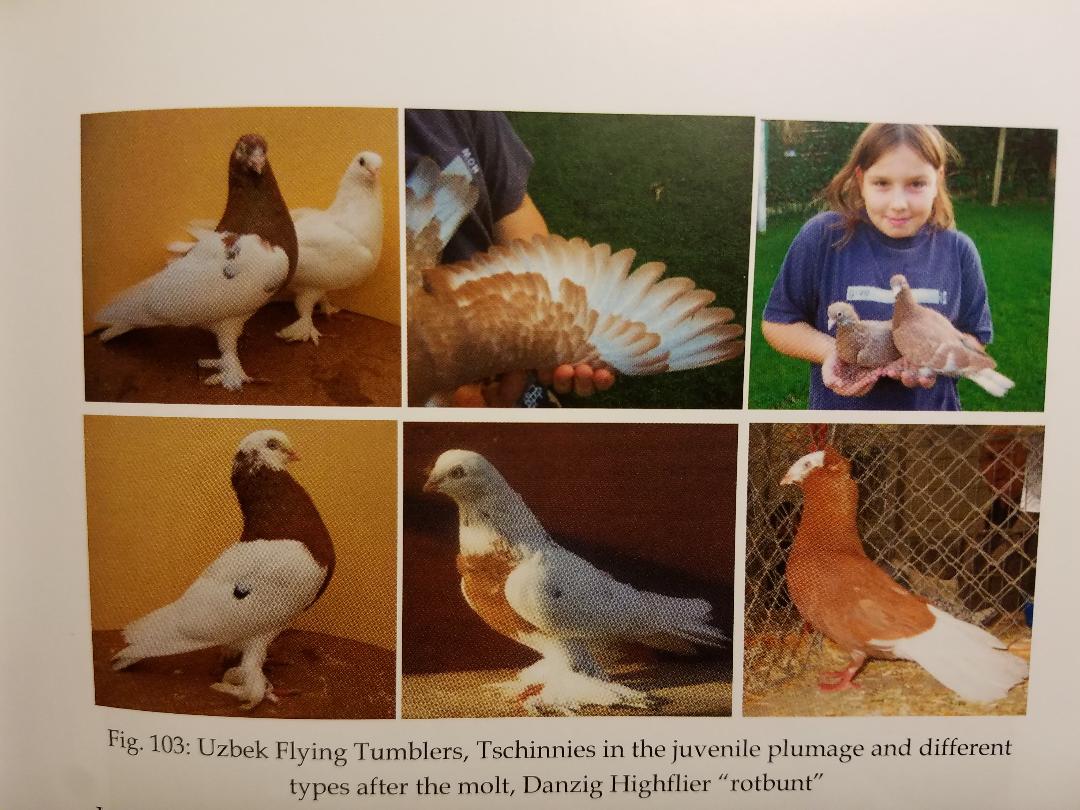

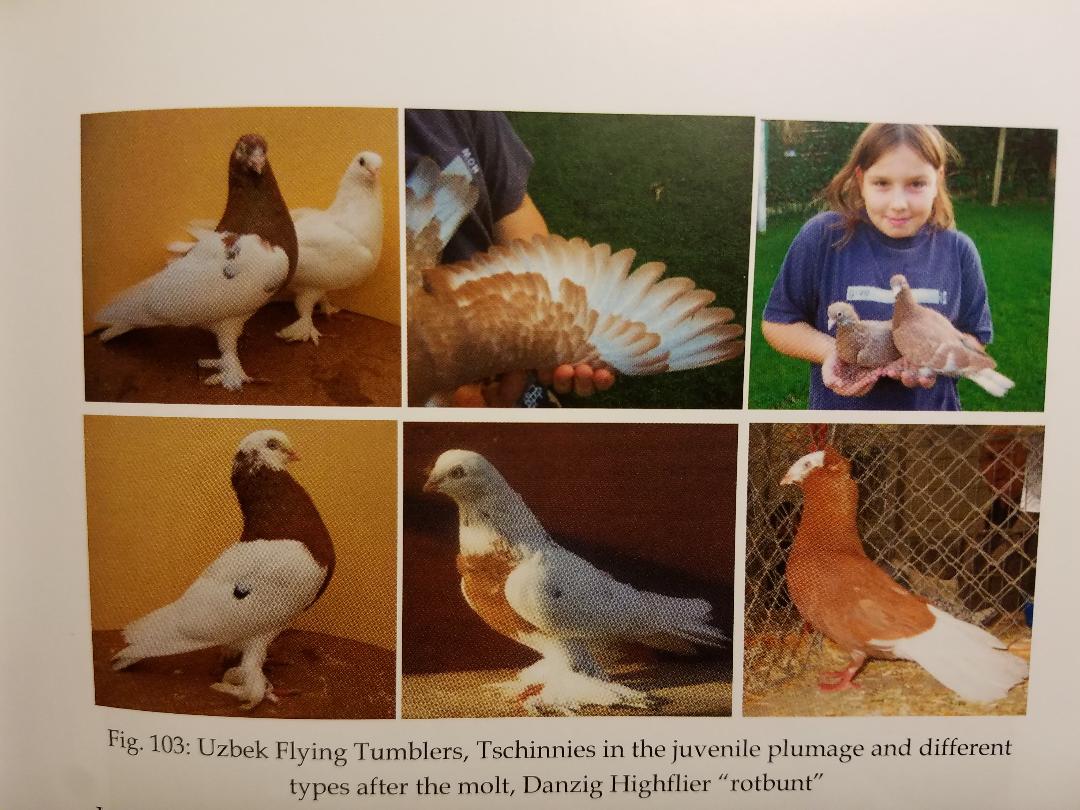

**IMPORTANT NOTE: There is a color variety of Uzbek Tumbler called a “Tschinnie” that is native to the Ottoman area (modern day Turkey etc.) that is Recessive Red and molts to either pure white or various beautiful predictable patterns of red and white with the first molt. The Krasnodar Tumbler is another. There is a description of Tschinnies in Axel Sell’s book “Pigeon Genetics,” pp. 130-132. In personal email conversation with Dr. Sell he acknowledges that the genetic similarities between Seraphim and Tschinnies cannot be ignored, as they both are Recessive Red with the Tail-Whitening and White-Sides trait, and the Oriental Frill and Uzbek Tumbler breeds arose in the same area of the world.

The Tschinnie colored Uzbek Tumbler may be the ancestral source of the recessive red and all of the whitening genes that exist in Seraphim today. In test crosses performed in 2006 by Andreas Leif on the Redhead/Neck variety, the Redhead/Neck trait was found to be allelic to White-Sides; Leif also suspected that a dominant enabler (switch) was required for expression of both the Whitesides and Redhead/Neck trait. (Photo from Axel Sell, “Pigeon Genetics,” page 131.

According to Mr. Sell there is anecdotal evidence that the Tschinnie color gene combination was deliberately crossed into Classic Oriental Frills, probably in the 1800’s. If this is true, then no matter how small the possibility, those linked Tschinnie genes were still floating around in the genetic pool of existing Classic Oriental Frills in the U.S., or Seraphim would not exist today. It could be predicted that Anne Ellis’s effort to make a Recessive Red Satinette Old-Fashioned Oriental Frill in 1986 using only the few existing Old-Fashioned Oriental Frills in the U.S. had a tiny chance to throw those Tschinnie color genes back together again. The Classic Oriental Frill had been essentially abandoned in the United States at that time and the breed was not recognized by the NPA, so the population was small. Everyone was breeding Modern Oriental Frills instead. Anne’s Recessive Red project caused her to seek high and low for Old-Fashioned Oriental Frills (as they were called then) and bring them to her loft because she needed to find the recessive red gene – if it existed in the population – and she needed genetic variability. She became distracted from her Recessive Red project by the Seraphim Project, however, when two babies with the Seraph Color Gene Complex appeared in her very first experimental nest meant to make a recessive red Satinette. (See the article on this site on The History of Seraphim.) She spent the next 30+ years working on refining the Seraphim breed instead of pursuing improved recessive red Satinette Classic Oriental Frills. Others became interested in the Old-Fashioned Classic Oriental Frill again because of Anne’s Seraphim Project, and Anne sold many of her Satinettes to other interested breeders including Harold Collett, who later established what is now the Classic Oriental Frill Club in 2003. Anne’s Seraphim project thus set the wheels in motion that both created Seraphim AND re-established the Classic Oriental Frill breed, which has today become so popular in the U.S. A Recessive Red Satinette, however, was not ever created by Ms. Ellis and could not be created from within the existing population of Classic Oriental Frills because a pure Recessive Red did not already exist within the population. Recessive Red DID exist in Moderns in the 1900’s, but the color was poor and impossible to maintain; it always faded with successive molts, leaving only a trace of pale red. Eventually an improved Recessive Red was bred into the existing Modern Oriental Frill population, solving their “Fading Red Problem.” Improved Recessive Red Classic Oriental Frills, however, were not created in the U.S. until just recently. Mike McLin succeeded in making high quality Recessive Red Classic Oriental Frills by using an outcross to a high – quality improved Recessive Red Modern Oriental Frill and aggressively culling the offspring. (“Making it More Interesting” by Mike McLin, Purebred Pigeon Magazine, March/April 2020, pp. 56-57.) Others may have had success using out-crosses as well but simply not published about it. Today improved Recessive Red is recognized in the Classic Oriental Frill in both Satinettes and Blondinettes. All of this historical information is important both for Seraphim fanciers and Classic Oriental Frill fanciers.

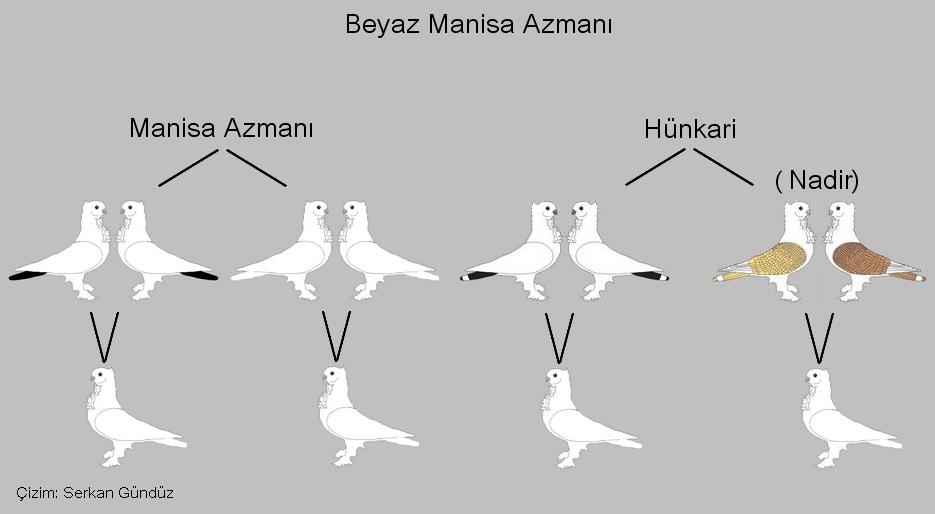

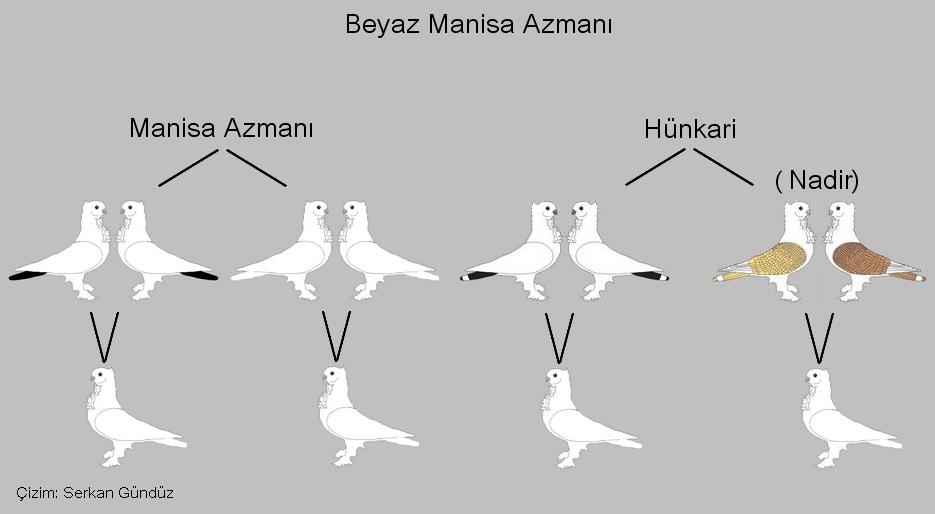

A very important recent development is a project in Turkey to recreate all the ancient color varieties of Classic Oriental Frills – “Hunkari” in Turkish. One such variety is called “Manisa Azmani.” They are pure white with colored tails, but one color strain is completely white. The project to re-establish all of the ancient color varieties of Classic Oriental Frills is headed up by Turker Savas and championed by Serkan Gunduz of Salihli, Turkey. Below is a photo of a Manisa Azmani, white with a colored tail. We do not have this color variety in the United States. Note that the structure of the Manisa Azmani below is that of the Show Standard for a very high quality Classic Oriental Frill.

Below is a diagram of all the color types of Manisa Azmani, summarized by Serkan Gunduz. Note that they include both smooth head and peaks. The smooth head style is not included in the United States Standard for Classic Oriental Frills in any color. Also note the pure white Manisa Azmani in the top row, second from the left. The drawing looks very much like the Show Standard for Seraphim. I have never seen a pure white Manisa Azmani, but it could be very difficult to distinguish from a Seraph. The color genetics are different, however, as the white Manisa Azmani is pure white from the beginning (conversation with Serkan), whereas the Seraph is red-marked at first, and then molts to pure white.

Here below is a diagram showing the various parental combinations of Manisa Azmani and Hunkari that are known to produce pure white youngsters. White paired to white always produces white. I do not know how often a white baby appears in the case of the other pairings. Serkan tells me that due to the popularity of all the other colors of Classic Oriental Frills in Turkey, white fell out of favor and became hard to find.

Below is a baby Seraph, red and white in the Satinette (Kanat) pattern. In comparison, the baby white Manisa Asmani or Hunkari would be completely white at this stage.

Adult Seraph, below. Aside from structural differences, it would be nearly impossible to distinguish this adult Seraph from an adult white Manisa Azmani unless you have a good eye and raised them yourself and confirmed the color of the birds as juveniles. The structural differences for Seraphim are due to decades of selective breeding to create a bird with a more vertical stance and a longer visual line. (See The Importance of Selective Breeding a few paragraphs below.)

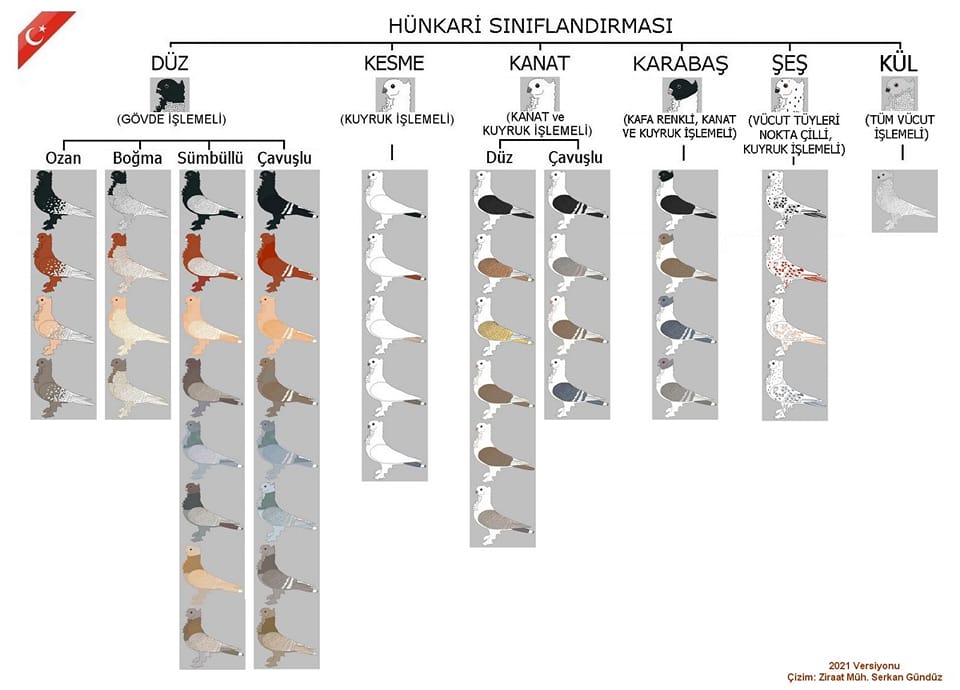

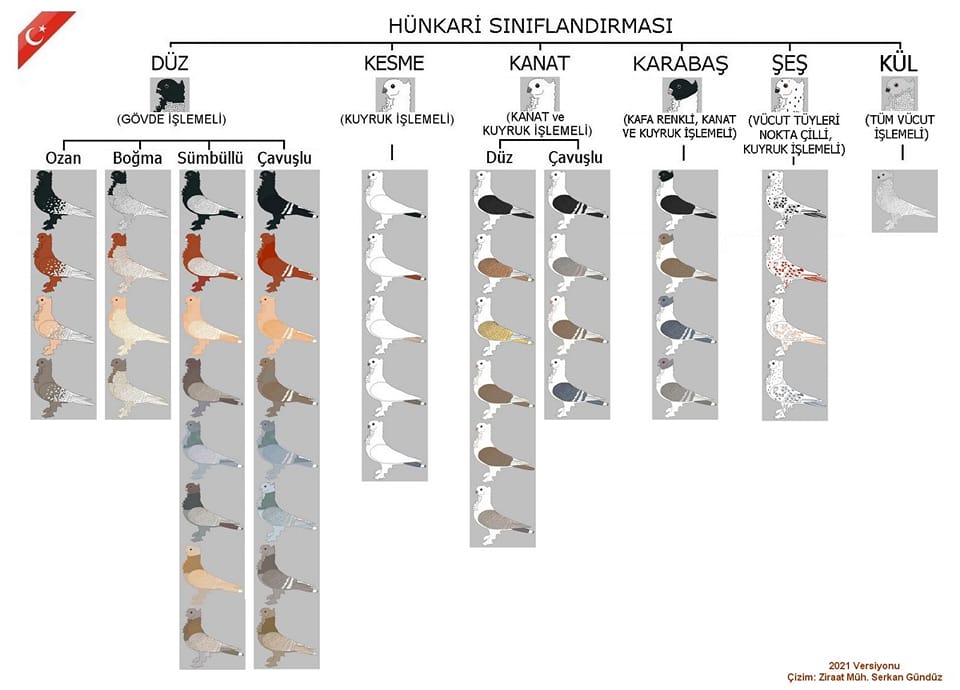

Below is another diagram by Serkan Gunduz showing most of the known color varieties and patterns of Hunkari (Classic Oriental Frill). There are even more ancestral color variations within each category than are depicted here. The Turkish team working on recreating these colors (and more) tells me that they have seen a couple Manisa Azmani with recessive red that fades gradually with successive molts without ever going completely white, which seems to be the same “fading red problem” that was such an issue here in the United States in the 1900’s. They have not seen anything that behaves like the Seraphim Color Gene Complex in Classic Oriental Frills there. I think the work that Turken and Serkan and their colleagues are doing to recreate and organize all of these categories of color genetics is very important and should be studied very carefully by the American Classic Oriental Frill Club.

The purpose of the above discussion on color is to explain the color genetics of Seraphim and to convincingly demonstrate that Seraphim have a specific set of color gene mutations that are not known or seen today in the ancestral Classic Oriental Frill population in Asia Minor (Turkey and the surrounding regions), and particularly in the white Classic Oriental Frills found there. My research has led me to believe that the Tschinnie Uzbek Tumbler, used as an outcross for color two hundred years ago or more, is probably the source of the genetic mutations that cause Seraphim to turn white with the first molt. In particular, I think it was the red head/neck variety of Tschinnie; the breeding tests by Tim Kvidera in the 1990’s on Seraphim outcrossed to pure recessive red produced a variety of color patterns confirming the role of the White Sides and Tail Whitening mutations, but one color combination that kept showing up was a white bird with red in the head, neck, or chest. (Conversation with Anne Ellis; See The Story of Seraphim for details.) Seraphim color and structure genetics cannot be understood without understanding the history of color and structure in Classic Oriental Frills and the Tschinnie Uzbek Tumbler.

SUMMARY:

Going forward, for the sake of simplicity, we’re going to think about the Seraphim Color Gene Complex as a combination of genes inherited together as if they are a single entity rather than multiple genes and gene switches. It makes it easier to think about breeding them if one understands that although the Seraphim Color Gene Complex is many genes, mutations, and modifiers, it will always come through as if it were a single recessive gene as long as Seraphim are bred only to each other.

So, to review. Recessive Red, White-Sides, and the Tail-Whitening mutation were inadvertently recombined and overlaid on Satinette (Piebald, Dominant White Flight) in 1986 in two offspring of a pair of Classic Oriental Frills in the loft of Anne Ellis, creating the first two “Seraphim.” Though this was something new – a recessive red Satinette Classic Oriental Frill that molted to white with the first molt – the color changing mutations probably came from something old, the Tschinnie Uzbek Tumblers of at least two hundred years ago, and the mutations may somehow be linked to cause the abrupt transition to white. Anne went on to spend decades creating the new breed – Seraphim – from those two original birds, using selective breeding to gradually morph them into what they are today. (See The 2017 Show Standard for details. See below for more information on selective breeding.)

The visual conversion from recessive red Satinette pattern to pure white is the result of the expression of the Seraphim Color Gene Complex – Satinette Piebald, Dominant White Flight, Recessive Red, the White-Sides mutation, and the Tail-Whitening mutation. This color mutation combination is an absolute defining trait for Seraphim.

THE IMPORTANCE OF SELECTIVE BREEDING:

In order to create a new breed, separate from the ancestral breed of origin, the Classic Oriental Frill, a vigorous program was begun by Anne Ellis in 1986 to create a bird with the Seraphim Color Gene Complex that is structurally substantially different than the Classic Oriental Frill. Genetics come into play here, but it is much more difficult to change structure than add color mutations, as structure is affected by more subtle genetic variability and influenced by the environment, nutrition, and epigenetics. It takes a careful eye and a long time to change structure. Anne imagined what she wanted Seraphim to look like and then selected the traits she needed from existing Classic Oriental Frills. Once the traits were obtained, selective breeding was continued within the new population of Seraphim to reinforce and refine the desired traits, making the Seraph what it is today, nearly forty years later.

Selective breeding for decades has given Seraphim an unusually beautiful, long flowing line. A narrower frame, a smooth concavity across the shoulders, increased height, a taller stance, and a rounded and larger head give it a look that is distinctly different from is breed of origin. Close attention to feather quality increased the overall feather length and frilliness. The toe feathers are longer, more refined and delicate; the swoop and mane are deeper; the needlepoint peak has been moved down below the top of the head; the frill is larger and fuller, and the tail and primary flights are long, adding to the long slender line of the bird. Their line makes them look fast and aerodynamic. They also appear more androgenous; it is difficult to tell the sexes apart by size or general appearance, as their masculine and feminine traits have been deliberately balanced to make each bird a showy piece of art regardless of sex. All of the structural changes are easy to see when comparing the 2017 Show Standard for Seraphim (above) to today’s Show Standard for the Classic Oriental Frill (See image below.) Since 1986 the structural differences between the two breeds have become increasingly evident as both have been modified by different goals of selective breeding. The Seraph is a breed that stands on its own.

Some argue that Seraphim are “just white Classic Old Frills.” This is a false argument I want to address head-on. Seraphim are a breed developed from the Classic Old Frill, but they are not “just” white Classic Old Frills. Seraphim have their own specific color genetics, and the Show Standards for the two breeds are completely different due to different goals in selective breeding for structure over the past forty years, as explained above. This should be obvious with even a cursory look at the images of the Standards for the two breeds. To actually find a true white Classic Oriental Frill that adheres to the Classic Oriental Frill Show Standard one would have to travel to Turkey, the only place I know where such birds exist today as Manisa Asmani. There are no white Classic Oriental Frills in the United States, and white is not a recognized color in the United States for Classic Oriental Frills. We can agree that Seraphim come from a limited genetic pool of ancestral Classic Oriental Frills and have the same basic genetic makeup, but we cannot agree that Seraphim are “just” white Classic Oriental Frills. Such a viewpoint completely ignores both the unique color genes and the nearly forty years of selective breeding done to create a bird that is distinctly different in appearance than the Classic Oriental Frill. After all, every breed that exists today has been developed from an already existing breed or a combination of existing breeds through careful selective breeding. Color is only part of the picture. One would not argue that all breeds of Pouters are “just a Pouter,” or that all breeds of Modenas are “just a Modena,” or that a Chinese Owl is “just an Old German Owl,” or that an Archangel is “just a Field Pigeon” without completely belittling all the work done by the originators and developers of those breeds which are admired and cultivated today. Without selective breeding, ALL fancy pigeon breeds would die out or revert back to their ancestral type. Seraphim are no different. They were invented over time, like all the other breeds, for a specific reason, from an already existing ancient breed. Serious and respectful pigeon fanciers respect the work others have done for breed development and will always breed toward the Show Standard for their breed, with recognition and understanding of the ancestral foundation upon which they are working.

BASIC PIGEON COLOR GENETICS FOR THE BEGINNER

(Please note the links in this article to Wikipedia entries and other sources that can be helpful. This can all be very difficult even when stated as simply as possible! Yet some basic understanding of these principles is necessary for the breeder of any Fancy Pigeon. The National Pigeon Association website has in-depth articles on pigeon genetics for those who wish to immerse themselves.)

CHROMOSOMES: The pigeon has forty pairs of chromosomes (or eighty individual chromosomes). Unlike other cells in the body, the sperm and the egg each have just forty individual chromosomes, or half the total, thanks to a process called meiosis which occurs only in testes and ovaries. When fertilization occurs and the sperm penetrates the nucleus of the egg, each sperm chromosome finds it’s match in the egg nucleus and pairs up with it. The fertilized egg now has a complete complement of forty paired chromosomes, or eighty total chromosomes, a normal pigeon cell. That cell immediately begins to divide using a new process called mitosis in which all of the chromosomes are duplicated just before division so that each division results in two cells with the full complement of eighty chromosomes. A great deal is now known about how this initial cell becomes an embryo and then a fully developed chick, but the details are too complex to discuss here. Enormous textbooks are written on the subject, and every day massive dissertations as well! It is wonderfully complex and amazing.

Anyway. During meiosis the various genes on the individual chromosomes remain reasonably consistent, but variation exists in the proteins that make up the DNA in those genes. Every time a new egg or sperm is formed there is the possibility that its chromosomes carry tiny changes in the order, or sequence, of the DNA proteins in the various gene segments. It is this possibility for change (mutation) that results in genetic variability, or differences that may be seen in the fully formed organism.

“Dominant” genes are segments of DNA that always express themselves over any mutation of the same gene sitting on the opposite paired chromosome. For instance, if a mother donates a gene for blue eyes and a father donates a gene for brown eyes, the child will always have brown eyes; brown always dominates any other eye color. The blue gene is there, but it is not visually expressed; it is “hidden” and will only show up if given a chance to pair up with another blue gene in the next generation. That blue gene may be passed on for several generations before finally getting the chance to appear when matched up with another person also carrying at least one blue gene. The blue gene is thus “recessed,” – or hidden – a “recessive” gene. It may also be called a recessive “trait”, or “characteristic.” Recessive genes or traits become important only when both parents carry them, as therein lies the only possibility for them to be expressed or seen.

“Partial Dominant”, or “Dominant with Variable Penetrance” are terms used to describe genes that are always expressed – but to a variable degree – when present, depending upon the effect of other genetic conditions present. Feathered legs and feet are an example of this phenomenon. The gene that causes this is dominant to the bare leg gene, but the variability in the penetrance – or visual expression – of the gene can result in anything from enormous leg “muffs” to “slipper” feathers to “grouse” feathers to “stubble” and anything in-between, depending upon other gene modifiers present that add to, or subtract from, the degree to which feather growth on the feet or legs is allowed.

There is also something called linkage. Sometimes genes are locked together and are passed on as a group that cannot be broken apart by the process of cell division and meiosis. In such instances, these linked genes are always expressed together at the same time, so for all intents and purposes the combination acts as if it is a single gene in the way it is passed on or inherited. Linkage may be partially responsible for some of the way color is passed on in Seraphim.

So, let’s review. Now you understand that each parent bird passes on half of its set of chromosomes in the egg or sperm so that the new chick has a full set of chromosomes – half of them from each parent. You also understand that some dominate genes on chromosomes overpower or dominate weaker recessive genes at the same location on the opposite paired chromosome; the paired chromosomes may carry a recessive gene each, a dominant gene each, or a combo of recessive and dominant. As Dominant always wins, the only time you can see hidden recessive traits is when they are on both chromosomes in the pair, so the trait has to come from each parent to appear. Linked gene combinations transfer multiple traits to the offspring all at once, and always together, so for all intents and purposes linked genes are inherited as if they are a single gene or trait.

SPECIAL CHROMOSOMES: So, let’s go back to those forty pairs of chromosomes once again. One of those pairs has a very special function: it determines the sex of the bird. This pair has a special name: sex chromosomes. The other thirty-nine pairs of chromosomes are called autosomal chromosomes, and they program almost everything else in pigeon development with a few exceptions.

In Pigeons the sex chromosomes are called Z and W. The hen is ZW and the cock is ZZ. So, the W sex chromosome is responsible for creating the female sex. The hen thus determines the sex of the chick through the egg. If she donates a Z, it will be a cock. If she donates a W, it will be a hen. By chance, half her eggs will carry a Z and half will carry a W; the eggs with W will produce hens. The cock can only contribute one of his two Z’s, since that’s all he has. In pigeons, the genes for the primary base color of the feathers – Ash Red, Brown, and Blue – are also located on the Z sex chromosome. Ash Red is dominate to Blue and Brown, Blue is only dominate to brown, and Brown is recessive to both Ash Red and Blue. This knowledge can be a useful tool. Since the hen has only one Z, a breeder KNOWS that she has just one basic color gene on her Z chromosome and can pass only that one color gene to ALL of her male offspring. Her color is also true – her appearance matches her one color-gene on her Z sex chromosome; if she is blue, she carries only blue, if she is ash red, she carries only ash red, if she is brown, she carries only brown; nothing is hidden from the eye. Her W does not carry a color gene, so her female offspring MUST have their base color determined by one of the two Z chromosomes from the cock, whichever one he contributes at fertilization. One can thus determine what colors the cock is carrying by the colors that are expressed in his female offspring. This is a general basic fact that can be helpful for all breeders.

I wish it were just that simple, but obviously there are other color-pigment and pattern altering genes present in pigeons or one wouldn’t see all of the different colors and patterns one sees at Fancy Pigeon Shows. Most of these color and pattern modifiers are located on the autosomal chromosomes (the 39 pairs of chromosomes that are not sex chromosomes) and a few on the single pair of sex chromosomes. No matter what color the pigeon appears to be, though, every pigeon has a base genetic color of ash-red, blue, or brown on the sex chromosomes, even if you can’t see it. The base colors can either be fully expressed, modified, or completely masked by color-modifying genes on the autosomal or sex chromosomes.

There are several books available on pigeon genetics that can be found on Amazon Books. Anyone breeding fancy pigeons seriously should be sure to avail themselves of such resources.